Non-Casino Games - FAQ

I like to play the game liars poker with dollar bills. what is the probability of getting any 1,2,3,4, or 5 of the same number on a bill. thank you. If I am playing with 3 people, what is the probability of any 1 number showing up.

First let me answer the unasked question on the probability that a specific number will show up n times on a random bill. There are 8 digits on a bill so the probability of n of a specific number is combin(8,n)*0.1n*0.98-n/108. Here is a table showing the probability for 0 to 8 of a specific number.

Specific Number Oddsin Liar's Poker

| Number | Probability |

|---|---|

| 8 | 0.00000001 |

| 7 | 0.00000072 |

| 6 | 0.00002268 |

| 5 | 0.00040824 |

| 4 | 0.00459270 |

| 3 | 0.03306744 |

| 2 | 0.14880348 |

| 1 | 0.38263752 |

| 0 | 0.43046721 |

| Total | 1.00000000 |

The next table shows the probability of every possible type of bill, categorized by the number of each n-of-a-kind. For example, the serial number 66847680 would have one three of a kind, one pair, and three singletons, for a probability of 0.1693440.

General Probabilities in Liar's Poker

| 8 o.a.k. | 7 o.a.k. | 6 o.a.k. | 5 o.a.k. | 4 o.a.k. | 3 o.a.k. | 2 o.a.k. | 1 o.a.k. | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0000001 | |||||||

| 1 | 1 | 0.0000072 | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | 0.0000252 | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 0.0002016 | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | 0.0000504 | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.0012096 | |||||

| 1 | 3 | 0.0028224 | ||||||

| 2 | 0.0000315 | |||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.0020160 | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 0.0015120 | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.0211680 | |||||

| 1 | 4 | 0.0211680 | ||||||

| 2 | 1 | 0.0020160 | ||||||

| 2 | 2 | 0.0141120 | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.0423360 | |||||

| 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.1693440 | |||||

| 1 | 5 | 0.0846720 | ||||||

| 4 | 0.0052920 | |||||||

| 3 | 2 | 0.1270080 | ||||||

| 2 | 4 | 0.3175200 | ||||||

| 1 | 6 | 0.1693440 | ||||||

| 8 | 0.0181440 | |||||||

| Total | 1.0000000 | |||||||

o.a.k. = "of a kind"

For more information, see my page on liars poker.

Bank of America is offering to triple a selected deposit a day made at an ATM. The contest is for about two months. Are my odds better when depositing $300 ... to make three deposits of $100 or one of $300...or are my overall odds so low that the difference isn't worth the effort?

Your expected win is the same regardless of how many times you divide your total deposits. A good strategy would be to deposit and withdraw the same money over and over as many times as possible. However, your odds may be so bad that it isn't worth the bother.

Just a question about an Oriental dice game, where the players are supposed to guess which side of the die shows up. The players will first place their bets on 1,2,3,4,5,6 (like roulette) and then the "dealer" will roll 3 dice simultaneously. Payouts are 1:1 if the chosen numbers shows up once (on any of the 3 dice), 2:1 if the chosen no shows up twice, and 3:1 if the chosen number appears on all 3 dice. As the player can place any number of bets of the board, what will be the optimum number of bets to place? (assuming all my bets are equal in size)

The probability of three matching is 1/216. The probability of two matching is 3*5/216. The probability of one matching is 25*5/216. The probability of 0 matching is 5*5*5/216. So the expected return is 3*(1/216)+2*(15/216)+1*(75/216)-1*(125/216)=-17/216=-7.87%. There is no optimal number of bets, you will give up an expected 7.87% of total money bet no matter what you do.

These bets can be made in both sic bo and chuck a luck.

What are the odds of winning a standard game of Klondike Solitaire as in the Windows version?

That is probably the most frequently asked question I get which I don't have an answer to. An exhaustive Klondike Solitaire has never been done. Maybe, when computers are a million times faster, somebody will eventually do it. However, it is rumored that Vegas casinos used to offer the game at least back in the fifties. I've asked a number of Vegas old-timers to verify that, but none have been able to, so far.

I recently rolled, during a game of backgammon, double sixes four consecutive times. What are the odds of this happening again?

With every new roll the probability the next four rolls will be all double sixes is (1/36)4 = 1 in 1679616.

Hi, at www.transience.com.au/pearl.html there is a game called Pearls for Swine. The pearls are grouped into three rows (5+4+3) ,and on your turn you may remove as many pearls as you like from one row. The object of the game is to leave the last of the pearls for your opponent to take. The player (me) always starts, (and always loses). Why do I never win? My opponent has a cunning system to always win, can you reveal his secret?

Start by removing 2 pearls from the row with 3, leaving 1+4+5. Regardless of what your opponent does on your next turn leave him with any of the following: 1+1+1, 1+2+3, or 4+4. From any of these force the opponent to a situation of two piles of 2 or more each, or an odd number of piles of 1 each.

What set in monopoly is the best?

I like the orange set the best. It offers the best return on investment. For example a hotel costs $500 on the orange set and the average rent is $966.67, for a rent to expense ratio of 1.93. The only set with a higher ratio is the light blue set, at 2.27. However the maximum rent on the light blues is only $600. The rents with three houses on the oranges are the same as the hotels on the light blues, but cost 20% less, with room to build more. Also, the oranges are ripe for landing on just coming out of jail. So take my advice and when trading try to get the orange set.

What is your advice for playing rocks/paper/scissors?

The best piece of advice anywhere on this site may be this: The first round, ALWAYS PICK PAPER. That is because amateur players tend to pick rock the first time. Just hold out your hand in each position, one at a time, and you’ll see that rock is the most comfortable and natural choice. If you play repeated rounds you should pick whatever would beat your opponent the last round with probability less than one-third. This is because I believe amateurs repeat less than one-third of the time. If playing a pro who you fear can get into your head then randomize by looking at the second hand of your watch, divide the number of seconds by three and take the remainder, then map the remaider as follows 0=rock, 1=scissors, 2=paper (or any other mapping as long as determined in advance). So the next time you go to a restaurant Dutch style I suggest playing a single round for the check and then pick paper. You can thank me later.

Who has the advantage in Risk when the attacker rolls three dice and the defender rolls two?

For those who aren’t familiar with the game, Risk is the greatest board game ever made. Those who haven’t played haven’t lived yet. To answer your question in the common 3 on 2 battle the following are the possible outcomes:

- Defender loses both: 37.17%

- Each loses one: 33.58%

- Attacker loses both: 29.26%

In the game of Yahtzee if only the Yahtzee itself is left on the card what is the probability of making it?

The following table shows the probability of success on the last roll according to the number of additional dice you need to make a Yahtzee.

Last Roll Yahtzee Probabilities

| Needed | Probability of Success |

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0.166667 |

| 2 | 0.027778 |

| 3 | 0.00463 |

| 4 | 0.000772 |

The next table shows the probabilities of improvement. The left column shows how many dice you need before any given roll and the top column shows how many you need after the roll. The body shows the probability of the given degree of improvement.

Probabilities of Improvement

| Need Before Roll | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0.166667 | 0.833333 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 0.027778 | 0.277778 | 0.694444 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 0.00463 | 0.069444 | 0.37037 | 0.555556 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 0.000772 | 0.01929 | 0.192901 | 0.694444 | 0.092593 | 1 |

The next table shows the probability on the initial roll of needing 0 to 4 more dice to make a Yahtzee.

First Roll Yahtzee Probabilities

| Needed | Probability |

| 0 | 0.000772 |

| 1 | 0.019290 |

| 2 | 0.192901 |

| 3 | 0.694444 |

| 4 | 0.092593 |

The next table shows the probability of improvement and then eventual success according to the number needed after the first roll. For example, if the player needs 3 more dice to make a Yahtzee the probability of improving to needing 2 more after the second roll and making the Yahtzee on the third roll is 0.010288066.

Probabilities of Yahtzee after first roll according to number needed before and after second roll

| Need Before Roll | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0.166667 | 0.138889 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.305556 |

| 2 | 0.027778 | 0.046296 | 0.01929 | 0 | 0 | 0.093364 |

| 3 | 0.00463 | 0.011574 | 0.010288 | 0.002572 | 0 | 0.029064 |

| 4 | 0.000772 | 0.003215 | 0.005358 | 0.003215 | 0.000071 | 0.012631 |

To get the final answer take the dot product of the number needed after the first roll two tables up and the probability of eventual success in the final column one table up. This is 0.092593*0.012631+ 0.694444*0.029064 + 0.192901*0.093364 + 0.019290*0.305556 + 0.000772*1 = 4.6028643%. To confirm this I did a 100,000,000 game simulation and the simulated probability was 4.60562%.

If dynamite is introduced as an option in the game of rock/paper/scissors, where dynamite beats rock and paper, but scissors beats dynamite, what should the optimal strategy be if two perfect logicians are playing?

First, we can rule out ever playing paper. Regardless of what the other person throws you will make out equal or better by throwing dynamite over paper. Once paper is eliminated, dynamite essentially becomes the new paper, beating rock and losing to scissors. So the perfect strategy is to pick randomly, and with equal probability, between rock, scissors, and dynamite.

What is the best strategy in one of those booths with the money that blows around while you have to collect as much as possible in a limited amount of time?

I asked this question to Randy Hill of Fun Industries Inc.. He said you should hold your arms straight out, palms down, and let the money blow up against the bottom of your hands and arms. When enough has accumulated you stuff it through the slot.

Suppose we have a gambling game. An unbiased coin flipped repeatedly. For each flip, we have to pay 1 rupee. There are two possible outcomes H or T. If the difference between head tossed and tail tossed becomes 3, we will get 8 rupee from the gambler. Should we play the game, and why? How much is our probability of winning? What should be impact on probability of winning when we are getting 7 or 9 rupees?

Lets call x the expected number of flips from the starting point.

Lets call y the expected number of remaining flips if one side is one flip in the majority.

Lets call z the expected number of remaining flips if one side is two flips in the majority.

E(x) = 1 + E(y)

E(y) = 1 + 0.5*E(x) + 0.5*E(z)

E(z) = 1 + 0.5*E(y)

It is then easy matrix algebra to see that E(x) = 9, E(y) = 8, and E(z) = 5. So on average it will take 9 flips for the disparity between heads and tails to be 3. So at 8 rupees it is a good bet for the person collecting the one rupee per flip, because he will receive on average 9 rupees, but pay back only 8. The house edge for the gambler is 11.11%. At 9 rupees it is a fair bet, at 7 the house advantage is 22.22%.

In your Nov 28, 2002 column you addressed the proper strategy for the game Pearls Before Swine. They also have a sequel called Pearls Before Swine II. How do I beat this version?

I explain in the 11/28/02 column how to play once there are only three rows left. Here is my strategy for four rows. When it is your turn look up the configuration along the left column and play what is on the right column. For example the starting position of 3456 is listed last and shows you should remove 4 pearls from the row with 5, leaving 1346. If the left column says "Lose" there is no way to win if the opponent plays optimal strategy, which the game at Transcience always seems to do.

A pattern to this table seems to be that you should force the opponent to a situation where the sum of the pearls in the smallest and greatest rows equals the sum of the two in the middle. This would include leaving zero in the row with the least number of pearls.

Pearls Before Swine II Strategy

| You Have | Leave |

| 1111 | 111 |

| 1112 | 111 |

| 1113 | 111 |

| 1114 | 111 |

| 1115 | 111 |

| 1116 | 111 |

| 1122 | Lose |

| 1123 | 1122 |

| 1124 | 1122 |

| 1125 | 1122 |

| 1126 | 1122 |

| 1133 | Lose |

| 1134 | 1133 |

| 1135 | 1133 |

| 1136 | 1133 |

| 1144 | Lose |

| 1145 | 1144 |

| 1146 | 1144 |

| 1155 | Lose |

| 1156 | 1155 |

| 1222 | 1122 |

| 1223 | 1122 |

| 1224 | 1122 |

| 1225 | 1122 |

| 1226 | 1122 |

| 1233 | 123 |

| 1234 | 123 |

| 1235 | 123 |

| 1236 | 123 |

| 1244 | 1144 |

| 1245 | 145 |

| 1246 | 246 |

| 1255 | 1155 |

| 1256 | Lose |

| 1333 | 1133 |

| 1334 | 1133 |

| 1335 | 1133 |

| 1336 | 1133 |

| 1344 | 1144 |

| 1345 | 145 |

| 1346 | Lose |

| 1355 | 1155 |

| 1356 | 1256 |

| 1444 | 1144 |

| 1445 | 1144 |

| 1446 | 1144 |

| 1455 | 1155 |

| 1456 | 1346 |

| 2222 | Lose |

| 2223 | 2222 |

| 2224 | 2222 |

| 2225 | 2222 |

| 2226 | 2222 |

| 2233 | Lose |

| 2234 | 2233 |

| 2235 | 2233 |

| 2236 | 2233 |

| 2244 | Lose |

| 2245 | 2244 |

| 2246 | 2244 |

| 2255 | Lose |

| 2256 | 2255 |

| 2333 | 2233 |

| 2334 | 2233 |

| 2335 | 2233 |

| 2336 | 2233 |

| 2344 | 2244 |

| 2345 | Lose |

| 2346 | 1346 |

| 2355 | 2255 |

| 2356 | 2345 |

| 2444 | 2244 |

| 2445 | 2244 |

| 2446 | 2244 |

| 2455 | 2255 |

| 2456 | 2345 |

| 3333 | Lose |

| 3334 | 3333 |

| 3335 | 3333 |

| 3335 | 3333 |

| 3336 | 3333 |

| 3344 | Lose |

| 3345 | 3344 |

| 3346 | 3344 |

| 3355 | Lose |

| 3356 | 3355 |

| 3444 | 3344 |

| 3445 | 3344 |

| 3446 | 3344 |

| 3455 | 3355 |

| 3456 | 1346 |

Brad S. wrote in to add a general strategy for any number of pearls and rows. First you break down each row into its binary components. For example the starting position of the Transcience game would be as follows.

- 3 = 2+1

- 4 = 4

- 5 = 4+1

- 6 = 4+2

Then you endeavor to leave an even number of each power of 2. For example in the above there are two 1’s, two 2’s, and three 4’s. So there is an extra 4. You then remove 4 from any of the rows with a 4 term. Keep doing this until you can get your opponent down to 2,2 or an odd number of 1’s.

Try this strategy on the Pearl 3 game, you’ll win every time. If you start with a losing scenario as I did on game 10 (4+7+8+11) you can click on "go" to make him go first.

Je ne pas compre your NIM game! I always thought the key to winning is to leave your opponent (in this case, the computer) with dots that add up to the next lowest number that equals its summary in binary numbers, that is, if I have 17 dots, I take 2 and leave 15, the summary of binary numbers 1,2,4,8. But this doesn’t seem to work. Am I right or wrong?

You are on the right track with the binary numbers but that is not quite the winning strategy. First, if you can leave your opponent with an odd number of rows of one each then do so. Otherwise break down each row into its binary components. For example, 99 would be 64+32+2+1. Then add up the number of each component over all the rows. Then look for a play that will leave your opponent with an even number of all binary components over all the rows.

Let’s look at an example. Suppose it is your turn with the following scenario.

The following table breaks down each row into its binary components.

Player’s Turn 1

| Row | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

You can see that there is an odd number of ones, twos, fours, and sixteens. Clearly we need to get the row of 25 under 16 to eliminate the 16 unit. To keep the total of the binary components even we need to remove the 1, add a 2, add a 4, keep the 8, and remove the 16. That means the best play is 2+4+8=14 in the last row. Leaving 14 in the bottom row we have the following.

Computer’s Turn 1

| Row | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

The computer takes its turn, leaving us with this.

Here is the binary breakdown of that.

Player’s Turn 2

| Row | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

Here we need to remove a 2 and a 4, to get those totals even. There is only one row, the 14, which has both components. So remove 6 from that, leaving 8.

Computer’s Turn 2

| Row | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

The computer takes its turn, leaving us with this.

Now we need to change the 1, 4, and 8 columns.

Player’s Turn 3

| Row | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

That can be done by changing the row of 8 to 5 as follows.

Computer’s Turn 3

| Row | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

The computer takes its turn, leaving us with this.

Now we need to change the 2 and 4 totals.

Player’s Turn 4

| Row | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

This can be done by changing the 6 to a 0.

Computer’s Turn 4

| Row | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

The computer takes its turn, leaving us with this.

Now we need to change the 2s and 4s.

Player’s Turn 5

| Row | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

This can be accomplished by changing the row of 5 to 3. If you can ever get your opponent to an x,x,y,y situation you can’t help but win, if you can maintain the same situation until the end.

Computer’s Turn 5

| Row | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The next few moves I keep the computer on x,x,y,y patterns. Here the computer leaves me with 2,2,3,2; so I leave it with 2,2,2,2.

The computer then gives me 2,2,1,2. I leave it with 2,2,1,1.

The computer then leaves me with 2,2,1. I leave it with 2,2. If you can ever get your opponent to two equal rows you can’t help but win, just keep the rows equal.

The computer then leaves me with a single pile of 2, and I remove 1.

Here is the end of the game.

I recently acquired a carnival wheel that belonged to my great uncle, it’s about a hundred years old and I’m trying to develop a game around it. It’s numbered 1-60 in random order and it alternates black and red with a green star every fifteenth mark, could you help me outline how much the payoffs should be for each spin?

So there are 30 black, 30 red, and 4 green numbers. That would make the probability of black 30/64, red 30/64 and green 4/64. If the probability of an event is p then the fair odds are (1-p)/p to 1. So fair odds for any red would be (34/64)/(30/64) = 34 to 30 = 17 to 15. Same for black. The fair odds on green are (60/64)/(4/64) = 60 to 4 = 15 to 1. For a specific number the fair odds are (63/64)/(1/64) to 63 to 1.

I suggest paying 1 to 1 on red and black, 14 to 1 on green, and 60 to 1 on any individual number. One formula for the house edge is (t-a)/(t+1), where t is the true odds, and a is the actual odds. In this case the house edge on the red or black bet is (63-60)/(63+1) = 3/64 = 4.69%. On the green bet the house edge is (15-14)/(15+1) = 1/16 = 6.25%. On individual numbers the house edge is (63-60)/(63+1) = 3/64 = 4.69%.

In New York state they have Video Lottery Terminals (VLT’s) at off-track betting spots. You hear the term a machine is approaching it’s "Set Point" when a VP machine gets "hot" and deals winning hand after winning hand. This would explain why the same machine pays on one day and doesn’t want to know you on other days. Also, most of these machines will not allow you to lose a winning dealt hand. Throw it away and it will return the equivalent hand or better. What are your thoughts on this subject?

VLT’s are glorified pull-tab games. There is a predetermined pool of outcomes. When you play, the game picks an outcome from the pool at random, and displays the win to the player in the form of a slot machine or video poker game. Since the outcome is predestined, any element of skill is imaginary. For example, if you are dealt a royal flush and throw it away, you’ll get another one on the draw. Usually I say that in gambling the past doesn’t matter, but in this case there is an effect of removal. If you play one time and lose, then it will marginally improve the odds of the remaining game outcomes, until the supply of virtual pull-tabs is exhausted, and I presume the virtual drum is refilled. I believe that your hot and cold swings are just normal luck, and any predestination is imagined.

A reader later added the following to this topic.

I have a comment on your February 14 "Ask the Wizard" column (No. 183). It’s doesn’t really have anything to do with the question you answered. It’s just something you might find interesting.

Prior to the passing of Proposition 1A, that allowed to have full class 3 gaming, we had a small installation of VLT style for a couple of years. In our system, which was run by SDG (now part of Bally), the prize pool started with 4 million draws. When the pool was reduced and 2 million remained, the next pool of 4 million was added for a total pool of 6 million draws. When the pool was reduced to 2 million again, the process repeated.

What is the expected number of rolls needed to get a Yahtzee?

Assuming the player always holds the most represented number, the average is 11.09. Here is a table showing the distribution of the number of rolls over a random simulation of 82.6 million trials.

Yahtzee Experiment

| Rolls | Occurences | Probability |

| 1 | 63908 | 0.00077371 |

| 2 | 977954 | 0.0118396 |

| 3 | 2758635 | 0.0333975 |

| 4 | 4504806 | 0.0545376 |

| 5 | 5776444 | 0.0699327 |

| 6 | 6491538 | 0.0785901 |

| 7 | 6727992 | 0.0814527 |

| 8 | 6601612 | 0.0799227 |

| 9 | 6246388 | 0.0756221 |

| 10 | 5741778 | 0.0695131 |

| 11 | 5174553 | 0.0626459 |

| 12 | 4591986 | 0.0555931 |

| 13 | 4022755 | 0.0487016 |

| 14 | 3492745 | 0.042285 |

| 15 | 3008766 | 0.0364257 |

| 16 | 2577969 | 0.0312103 |

| 17 | 2193272 | 0.0265529 |

| 18 | 1864107 | 0.0225679 |

| 19 | 1575763 | 0.019077 |

| 20 | 1329971 | 0.0161013 |

| 21 | 1118788 | 0.0135446 |

| 22 | 940519 | 0.0113864 |

| 23 | 791107 | 0.00957757 |

| 24 | 661672 | 0.00801056 |

| 25 | 554937 | 0.00671837 |

| 26 | 463901 | 0.00561624 |

| 27 | 387339 | 0.00468933 |

| 28 | 324079 | 0.00392347 |

| 29 | 271321 | 0.00328476 |

| 30 | 225978 | 0.00273581 |

| 31 | 189012 | 0.00228828 |

| 32 | 157709 | 0.00190931 |

| 33 | 131845 | 0.00159619 |

| 34 | 109592 | 0.00132678 |

| 35 | 91327 | 0.00110565 |

| 36 | 76216 | 0.00092271 |

| 37 | 63433 | 0.00076795 |

| 38 | 52786 | 0.00063906 |

| 39 | 44122 | 0.00053417 |

| 40 | 36785 | 0.00044534 |

| 41 | 30834 | 0.00037329 |

| 42 | 25494 | 0.00030864 |

| 43 | 21170 | 0.0002563 |

| 44 | 17767 | 0.0002151 |

| 45 | 14657 | 0.00017745 |

| 46 | 12410 | 0.00015024 |

| 47 | 10299 | 0.00012469 |

| 48 | 8666 | 0.00010492 |

| 49 | 7355 | 0.00008904 |

| 50 | 5901 | 0.00007144 |

| 51 | 5017 | 0.00006074 |

| 52 | 4227 | 0.00005117 |

| 53 | 3452 | 0.00004179 |

| 54 | 2888 | 0.00003496 |

| 55 | 2470 | 0.0000299 |

| 56 | 2012 | 0.00002436 |

| 57 | 1626 | 0.00001969 |

| 58 | 1391 | 0.00001684 |

| 59 | 1135 | 0.00001374 |

| 60 | 924 | 0.00001119 |

| 61 | 840 | 0.00001017 |

| 62 | 694 | 0.0000084 |

| 63 | 534 | 0.00000646 |

| 64 | 498 | 0.00000603 |

| 65 | 372 | 0.0000045 |

| 66 | 316 | 0.00000383 |

| 67 | 286 | 0.00000346 |

| 68 | 224 | 0.00000271 |

| 69 | 197 | 0.00000238 |

| 70 | 160 | 0.00000194 |

| 71 | 125 | 0.00000151 |

| 72 | 86 | 0.00000104 |

| 73 | 79 | 0.00000096 |

| 74 | 94 | 0.00000114 |

| 75 | 70 | 0.00000085 |

| 76 | 64 | 0.00000077 |

| 77 | 38 | 0.00000046 |

| 78 | 42 | 0.00000051 |

| 79 | 27 | 0.00000033 |

| 80 | 33 | 0.0000004 |

| 81 | 16 | 0.00000019 |

| 82 | 18 | 0.00000022 |

| 83 | 19 | 0.00000023 |

| 84 | 14 | 0.00000017 |

| 85 | 6 | 0.00000007 |

| 86 | 4 | 0.00000005 |

| 87 | 9 | 0.00000011 |

| 88 | 4 | 0.00000005 |

| 89 | 5 | 0.00000006 |

| 90 | 5 | 0.00000006 |

| 91 | 1 | 0.00000001 |

| 92 | 6 | 0.00000007 |

| 93 | 1 | 0.00000001 |

| 94 | 3 | 0.00000004 |

| 95 | 1 | 0.00000001 |

| 96 | 1 | 0.00000001 |

| 97 | 2 | 0.00000002 |

| 102 | 1 | 0.00000001 |

| Total | 82600000 | 1 |

Do you know of any website that has a good analysis of backgammon odds/statistics/probability, and are there any particular books you can recommend on any aspect of the game?

Backgammon is one of my favorite gambling games. I don’t write about it because player vs. player games are extremely hard to analyze. I also can’t seem to find any new ground to break in the game. So, I’ll leave the advice to others. Here are my suggested resources:

Backgammon by Paul Magriel: If there were a Bible to backgammon, this would be it. I’m a proud owner of an old hard-cover edition. This book would be a great place to start. Although it was written in 1976, the advice still holds up well.

501 Essential Backgammon Problems by Bill Robertie: I’ve been trying to get through this book for years, and I’m still only half way there. It is disheartening to get half the problems wrong, enough to make me think I’m as bad at backgammon as I am at golf. However, with every problem missed, there is a valuable lesson to be learned. For the intermediate to advanced player, this book is a valuable, and humbling, learning tool.

Snowie backgammon software: I play about 1000 games a year against this game. Snowie not only plays a near-perfect game, but tells you exactly how costly your errors are, when you make them. There are lots of other features that I have never explored. If there is one thing I’ve learned from Snowie, it’s that the biggest problem with my game is bone-headed mistakes of not seeing perfectly obvious plays sometimes. Much like chess, one bad move can wipe out 100 good ones.

Motif website: Before I purchased Snowie, I played countless games against Motif. The strategy employed by Motif is very solid, in my opinion. There is nothing like playing against a stronger opponent to improve your own game.

In the April 11, 2004 column there is a question about proper strategy in the Price is Right Showcase Showdown. Assuming optimal strategy is followed, what is the probability of each player winning?

The following table shows the probability of each player winning, according to the first player’s first spin, where player 1 goes first, followed by player 2, and player 3 last. The bottom row shows the overall probabilities of winning, before the first spin.

Probabilities in the Price is Right Showcase Showdown

| Spin 1 | Strategy | Player 1 | Player 2 | Player 3 |

| 0.05 | spin | 20.59% | 37.55% | 41.85% |

| 0.10 | spin | 20.59% | 37.55% | 41.86% |

| 0.15 | spin | 20.57% | 37.55% | 41.87% |

| 0.20 | spin | 20.55% | 37.55% | 41.9% |

| 0.25 | spin | 20.5% | 37.56% | 41.94% |

| 0.30 | spin | 20.43% | 37.56% | 42.01% |

| 0.35 | spin | 20.33% | 37.58% | 42.10% |

| 0.40 | spin | 20.18% | 37.60% | 42.22% |

| 0.45 | spin | 19.97% | 37.64% | 42.39% |

| 0.50 | spin | 19.68% | 37.71% | 42.61% |

| 0.55 | spin | 19.26% | 37.81% | 42.93% |

| 0.60 | spin | 18.67% | 37.96% | 43.36% |

| 0.65 | spin | 17.86% | 38.21% | 43.93% |

| 0.70 | stay | 21.56% | 38.28% | 40.16% |

| 0.75 | stay | 28.42% | 35.21% | 36.38% |

| 0.80 | stay | 36.82% | 31.26% | 31.92% |

| 0.85 | stay | 46.99% | 26.35% | 26.66% |

| 0.90 | stay | 59.17% | 20.36% | 20.47% |

| 0.95 | stay | 73.61% | 13.19% | 13.21% |

| 1.00 | stay | 90.57% | 4.72% | 4.72% |

| Average | 30.82% | 32.96% | 36.22% |

Here are the winning number of combinations out of the 6×206 possible.

Player 1: 118,331,250Player 2: 126,566,457

Player 3: 139,102,293

What is the correct strategy for Acey Deucey at a home poker game? The way we play is if the third card matches one of the first two, then the bet is a push.

The way you play, where a third-card match is a push, the odds swing in your favor when there are at least six ranks between the first two cards (a six-card spread). The way I played in Orange County, a third-card match resulted in a double loss. Under that rule, the odds are break-even with an eight-card spread. If a third-card match results in a 1x loss, then you need a seven-card spread for the odds to be in your favor.

The game of one-card poker has a three-card deck, an ace, deuce, and trey. The ace is lowest and the trey is highest. Each of two players antes $1 into the pot. Then, each player gets one card. The order of betting is predetermined, with player 1 to act first. Player 1 may either bet $1 or check. If player 1 bets, player 2 may either call or fold. If player 1 checks, then player 2 may either bet $1 or check. If player 1 checks, and player 2 bets, then player 1 may either call or fold. If both players check, or both bet, then the higher card wins the pot. Assuming both players are perfect logicians, what is the optimal strategy for each player?

I hope you’re happy; I spent all day on this. The answer and solution can be found on my other site mathproblems.info, problem 203, or the academic paper Game Theory and Poker by Jason Swanson.

I’m shopping around for a mortgage. One company is offering an interest rate of 5.75%, plus one point, on a 30-year fixed. Another is charging 5.875% without a point. Which is the better offer?

For the benefit of other readers, a point is a commission charged for the loan. For example, on a $250,000 loan one point would be $2,500. I’m going to assume that the borrower would add the point to the principal balance, and never pay down the principle early.

The following table shows the equivalent interest rate without the point, according to the interest rate with one point and the term.

Equivalent Interest Rate with No Points

| Interest Rate with One Point | 10 years | 15 years | 20 years | 30 years | 40 years |

| 4.00% | 4.212% | 4.147% | 4.115% | 4.083% | 4.067% |

| 4.25% | 4.463% | 4.398% | 4.366% | 4.334% | 4.318% |

| 4.50% | 4.714% | 4.649% | 4.617% | 4.585% | 4.570% |

| 4.75% | 4.965% | 4.900% | 4.868% | 4.836% | 4.821% |

| 5.00% | 5.216% | 5.151% | 5.119% | 5.088% | 5.073% |

| 5.25% | 5.467% | 5.402% | 5.370% | 5.339% | 5.324% |

| 5.50% | 5.718% | 5.654% | 5.621% | 5.590% | 5.576% |

| 5.75% | 5.969% | 5.905% | 5.873% | 5.842% | 5.827% |

| 6.00% | 6.220% | 6.156% | 6.124% | 6.093% | 6.079% |

| 6.25% | 6.471% | 6.407% | 6.375% | 6.344% | 6.330% |

| 6.50% | 6.723% | 6.658% | 6.626% | 6.596% | 6.582% |

| 6.75% | 6.974% | 6.909% | 6.878% | 6.847% | 6.834% |

| 7.00% | 7.225% | 7.160% | 7.129% | 7.099% | 7.085% |

| 7.25% | 7.476% | 7.412% | 7.380% | 7.350% | 7.337% |

| 7.50% | 7.727% | 7.663% | 7.631% | 7.602% | 7.589% |

| 7.75% | 7.978% | 7.914% | 7.883% | 7.853% | 7.841% |

| 8.00% | 8.229% | 8.165% | 8.134% | 8.105% | 8.093% |

| 8.25% | 8.480% | 8.416% | 8.385% | 8.357% | 8.344% |

| 8.50% | 8.731% | 8.668% | 8.637% | 8.608% | 8.596% |

| 8.75% | 8.982% | 8.919% | 8.888% | 8.860% | 8.848% |

| 9.00% | 9.233% | 9.170% | 9.140% | 9.112% | 9.100% |

| 9.25% | 9.485% | 9.421% | 9.391% | 9.363% | 9.352% |

| 9.50% | 9.736% | 9.673% | 9.642% | 9.615% | 9.604% |

| 9.75% | 9.987% | 9.924% | 9.894% | 9.867% | 9.856% |

| 10.00% | 10.238% | 10.175% | 10.145% | 10.119% | 10.108% |

This shows that a 5.75% interest rate with one point is equivalent to a 5.842% with no points. In other words the payment would be the same both ways, assuming the point charged is added to the principal balance. Your other offer was 5.875% with no points, which is higher than 5.842%, so I would take the 5.75% with the point.

P.S. For those of you wondering how I solved for i, I used the rate function in Excel.

My son just made two holes in one, in the span of 2 weeks. What are the odds. My son has a 1 handicap. the 1st 151 yards and the 2nd 137 yards, at two different courses.

According to Life: the Odds (and How to Improve Them) by Gregory Baer, the odds of a hole in one on a par 3 hole in the PGA tour is 1 in 2491. I believe those distances fall in the par 3 range.

A 1 handicap is darn good, so I'm not going to give much of a discount compared to PGA Tour players. Let's say your son's probability per par 3 hole is 1 in 3,000. A typical gold course will have about four par 3 holes. Let’s say your son plays every day. That would be 28 par 3 holes a week. The probability of making exactly two hole in ones would be combin(28,2)×(1/3000)2×(2999/3000)26 = 1 in 24,017.

I recently entered a raffle where there are 7,033 prizes and they say the odds of winning a prize are 1 in 13. I bought 5 tickets. What are my actual odds of winning something? Also, there are 40 big prizes. What are my odds of winning a big prize?

For the sake of simplicity, let’s ignore the fact that the more tickets you buy the lower the value of each ticket becomes because you compete with yourself. That said, the probability of losing all five tickets is (12/13)5 = 67.02%. So the probability of winning at least one prize is 32.98%. There are 7033×13=91,429 total tickets in the drum before you buy any. 91,429-40=91,389 are not big prizes. The probability of not winning any big prizes with five tickets is (91,389/91429)5 = 99.78%. So the probability of winning at least one big prize is 0.22%, or 1 in 458.

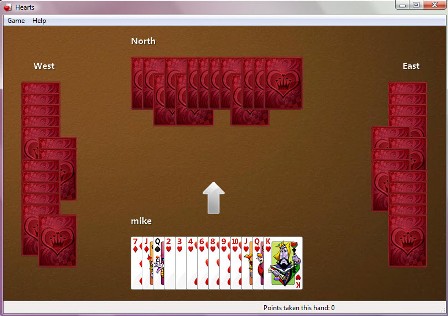

In the game of hearts, each player is given 13 cards. The suit with the most cards out of the 13 is called the "long suit," which can have 4 to 13 cards. What is the probability for each of these totals?

Probabilities for Long Suit in Hearts

| Cards | Combinations | Probability |

| 4 | 222766089260 | 0.35080524800183 |

| 5 | 281562853572 | 0.44339660045899 |

| 6 | 105080049360 | 0.16547685914958 |

| 7 | 22394644272 | 0.03526640326564 |

| 8 | 2963997036 | 0.00466761219692 |

| 9 | 235237860 | 0.00037044541245 |

| 10 | 10455016 | 0.00001646424055 |

| 11 | 231192 | 0.00000036407412 |

| 12 | 2028 | 0.00000000319363 |

| 13 | 4 | 0.00000000000630 |

| Total | 635013559600 | 1 |

The Rule of 72 states that you divide an annual rate of return into 72, and that gives you the number of years it will take to double your money. For instance, an investment that pays 10% annually will take 72/10=7.2 years to double in value. My somewhat idle question is, why 72?

First, the "rule of 72" is an approximation of the time needed to double your money, not an exact answer. The following table shows the "rule of 72" values and the exact number of years, for various annual interest rates.

Rule of 72 — Years to Double Money

| Interest Rate | Rule of 72 | Exact | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 72.00 | 69.66 | 2.34 |

| 0.02 | 36.00 | 35.00 | 1.00 |

| 0.03 | 24.00 | 23.45 | 0.55 |

| 0.04 | 18.00 | 17.67 | 0.33 |

| 0.05 | 14.40 | 14.21 | 0.19 |

| 0.06 | 12.00 | 11.90 | 0.10 |

| 0.07 | 10.29 | 10.24 | 0.04 |

| 0.08 | 9.00 | 9.01 | -0.01 |

| 0.09 | 8.00 | 8.04 | -0.04 |

| 0.10 | 7.20 | 7.27 | -0.07 |

| 0.11 | 6.55 | 6.64 | -0.10 |

| 0.12 | 6.00 | 6.12 | -0.12 |

| 0.13 | 5.54 | 5.67 | -0.13 |

| 0.14 | 5.14 | 5.29 | -0.15 |

| 0.15 | 4.80 | 4.96 | -0.16 |

| 0.16 | 4.50 | 4.67 | -0.17 |

| 0.17 | 4.24 | 4.41 | -0.18 |

| 0.18 | 4.00 | 4.19 | -0.19 |

| 0.19 | 3.79 | 3.98 | -0.20 |

| 0.20 | 3.60 | 3.80 | -0.20 |

Why 72? It doesn’t have to be exactly 72. That is just the number that works out well for realistic interest rates you’re likely to see on an investment. It works out almost exactly for an interest rate of 7.8469%. There is nothing special about 72, like there is about π or e. Why does any number work? If the interest rate is i, then let’s solve for the number of years (y) it takes to double an investment.

2 = (1+i)y

ln(2)= ln(1+i)y

ln(2)= y×ln(1+i)

y = ln(2)/ln(1+i)

This may not be my best answer ever, but try to follow this logic: let y=ln(x).

dy/dx=1/x.

1/x =~ x at values of x close to 1.

So the dy/dx =~ 1 for values of x close to 1.

So the slope of ln(x) is going to be close to 1 for values of x close 1.

So the slope of ln(1+x) is going to be close to 1 for values of x close 0.

The "rule of 72" is saying that .72/i =~ .6931/ln(1+i).

We’ve established that i and ln(1+i) are similar for values of i close to 0.

So 1/i and 1/ln(1+i) are similar for values of i close to 0.

Using 72 instead of 69.31 adjusts for differences between i and ln(1+i) for values of i around 8%.

I hope that makes some sense. My calculus is rather rusty; it took hours to explain this to myself.

This question was raised and discussed in the forum of my companion site Wizard of Vegas.

At a recent street fair, they had a game in which there was a field of numbers with shallow cups and a cup of balls and it involves addition. I didn’t ask the name of the game, and I searched the internet for about an hour but couldn’t find anything about it. I thought you might have some information about it, it’s odds, or at least the name.

The industry term for that game is Razzle Dazzle. I remember seeing it in southern California as a kid, and just last year in San Felipe, Mexico. It is usually skinned to look like a football game. This game is the worst of the carnival game scams, in my opinion. The state of New York should be ashamed for permitting it. Based on some research, the rules vary from place to place, but the gist of the con is always the same.

It is based on the same illusion as the field bet in craps. For those readers not familiar with the field bet, the player wins if the sum of the roll of two dice is 2, 3, 4, 9, 10, 11, or 12. Losing numbers are 5, 6, 7, and 8. Wins pay even money, except the 2 pays 2 to 1 and the 12 pays 3 to 1 (except at stingy Harrah’s casinos, where they pay 2 to 1 only on the 12). The mathematically challenged gambler may falsely reason it is a good bet because there are 7 totals that win and only 4 that lose. The reason the odds favor the house is that the losing numbers have the greatest chance to be rolled.

Here are the specific rules of Razzle Dazzle, as taken from the article Probabilities of Winning a Certain Carnival Game by Donald A. Berry and Ronald R. Regal, which appeared in the November 1978 issue of the The American Statistician.

- The object of the game is to advance across the football field 100 yards. The player will be awarded some kind of nice prize when he does.

- The player starts paying a specified fee per play, such as $1.

- The player will spill 8 marbles onto an 11 by 13 grid. Each marble will fall into one of the 143 holes.

- Each hole has a number of points from 1 to 6. The following table shows the frequency of each number of points.

Razzle Dazzle Points Distribution

Points Number

on BoardProbability 1 11 0.076923 2 19 0.132867 3 39 0.272727 4 44 0.307692 5 19 0.132867 6 11 0.076923 Total 143 1.000000 - The total number of points will be added. The carnie will look up the point total on a conversion chart to see how many yards the player advances. The conversion chart is shown below.

Razzle DazzleConversion Chart

Points Yards

Gained8 100 9 100 10 50 11 30 12 50 13 50 14 20 15 15 16 10 17 5 18 to 38 0 39 5 40 5 41 15 42 20 43 50 44 50 45 30 46 50 47 100 48 100 - If the player rolls a total of 29, then the fee for all subsequent rolls will be doubled, and the player be awarded one extra prize if and when he reaches the other end of the football field.

The average points per marble is 3.52, and the standard deviation is 1.31. Note how 3 and 4 points have the highest probability. That keeps the standard deviation low, and the sum of many marbles close to expectations. The standard deviation of the roll of a single die is 1.71, by comparison.

Next, notice how there are 20 winning totals and 21 losing totals on the yardage conversion chart. The kind of sucker who gambles on carnival games might incorrectly reason his probability of advance is 20/41 or 48.8%. It wouldn’t surprise me if the carnies falsely claimed these were the odds of advancing. However, much like the field bet, the most likely outcomes don’t win anything.

The next table show the probability of each number of points per turn, yards gained, and expected yards gained. The lower right cell shows the average yards gained per turn is 0.0196.

Expected Yards Gained per Turn

| Points | Probability | Yards Gained |

Expected Yards Gained |

| 8 | 0.00000000005 | 100 | 0.00000000464 |

| 9 | 0.00000000176 | 100 | 0.00000017647 |

| 10 | 0.00000002586 | 50 | 0.00000129285 |

| 11 | 0.00000022643 | 30 | 0.00000679305 |

| 12 | 0.00000143397 | 50 | 0.00007169849 |

| 13 | 0.00000713000 | 50 | 0.00035650022 |

| 14 | 0.00002926510 | 20 | 0.00058530196 |

| 15 | 0.00010234709 | 15 | 0.00153520642 |

| 16 | 0.00031168305 | 10 | 0.00311683054 |

| 17 | 0.00083981462 | 5 | 0.00419907311 |

| 18 | 0.00202563214 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 19 | 0.00441368617 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 20 | 0.00874847408 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 21 | 0.01586193216 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 22 | 0.02642117465 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 23 | 0.04056887936 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 24 | 0.05757346716 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 25 | 0.07566411880 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 26 | 0.09221675088 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 27 | 0.10431970222 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 28 | 0.10958441738 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 29 | 0.10689316272 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 30 | 0.09677806051 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 31 | 0.08125426057 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 32 | 0.06317871335 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 33 | 0.04540984887 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 34 | 0.03009743061 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 35 | 0.01833921711 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 36 | 0.01023355162 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 37 | 0.00520465303 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 38 | 0.00239815734 | 0 | 0.00000000000 |

| 39 | 0.00099365741 | 5 | 0.00496828705 |

| 40 | 0.00036673565 | 5 | 0.00183367827 |

| 41 | 0.00011909673 | 15 | 0.00178645089 |

| 42 | 0.00003349036 | 20 | 0.00066980729 |

| 43 | 0.00000797528 | 50 | 0.00039876403 |

| 44 | 0.00000155945 | 50 | 0.00007797235 |

| 45 | 0.00000023832 | 30 | 0.00000714969 |

| 46 | 0.00000002632 | 50 | 0.00000131607 |

| 47 | 0.00000000176 | 100 | 0.00000017647 |

| 48 | 0.00000000005 | 100 | 0.00000000464 |

| Totals | 1.00000000000 | 0 | 0.01961648451 |

Here are some results of a random simulation of 17.5 million games.

Razzle Dazzle Simulation Results

| Question | Answer |

| Probability of advancement per turn | 0.0028 |

| Expected yards gained per turn | 0.0196 |

| Expected yards gained per advancement | 6.9698 |

| Expected turns per game | 5238.7950 |

| Average doubles per game | 559.9874 |

| Averages prizes per game | 560.9874 |

I would have liked to indicate the average total bet per game, but my computer can not handle numbers so large. The average game had the player doubling his bet 560 times over the average of 5,239 turns per game. One game in the simulation had the player doubling his bet 1,800 times. Even at the average of 560 doubles, the bet per roll would be $3.77 × 10168, assuming a starting bet of $1. That is many orders of magnitutude greater than the number of atoms in the known universe (source).

Even the most naive player will not play for long if he is advancing once every 355 plays only. What the carnies will do is cheat in the player’s favor at first. He may spot the player free rolls, or lie in adding up the points, giving the player winning totals to boost his confidence. I’ve never played the game, but I imagine that when the player gets close to the red zone (20 yards or less from a touchdown), then the carnie will start playing fairly. The player may wonder why he is suddenly getting nowhere, but with money already invested, and being so close to the goal line, he would hesitate to walk away and give up the yardage he already paid for.

Links

- Razzle Dazzle, excerpt from the book On the Midway.

- Razzle Dazzle Carny Board Game Arcade Scam.

- Probabilities of Winning a Certain Carnival Game by Donald A. Berry and Ronald R. Regal

A recent carnival was offering a tic tac toe style game. For £1 a go you throw three incredibly bouncy balls towards a large wooden box with 9 pockets in the bottom. Assuming every ball landed in a unique square, what would be the probability of winning?

There are eight ways two win: three rows, three columns, and two diagonals. There are combin(9,3)=84 ways to pick 3 squares out of 9. So the probability of winning is 8/84 = 9.52%.

This question was raised and discussed in the forum of my companion site Wizard of Vegas.

What is your advice for playing Monopoly?

Here is my Wizard’s basic strategy for Monopoly:

- Buy everything. Advanced players may make exceptions if the property won’t help you make a monopoly, block someone else, and has little value as a bargaining chip. Utilities can also be declined in a cash-poor situation.

- Trade as well as you can. This is where the skill comes in. Try to trade for the best set you can. Here is how I rank them, in general: Orange, Yellow, Light Blue, Dark Blue, Light Purple, Red, Green, Dark Purple. This will vary depending on circumstances. In a cash-poor game, favor the sets that are cheaper to develop, like the light blues. In a cash-rich game, go for the ones where there is more potential to spend money on, like the yellows or dark blues.

- Once you get a set, whether naturally or by trade, build up quickly. Try to get to three houses on each property as quickly as possible. The marginal return per house drops after three. Mortgage most of your other properties and spend your cash. You want to leave a little equity for small expenses. Not spending your money is like a soldier in battle not using his bullets.

- Oppose all the silly house rules. This especially goes for the money pot on Free Parking (I can’t stand that one!). If you are more skilled than your opponents, you want to minimize the randomness of the game.

If a monkey was playing with the Rubik’s Cube, what would be the odds of its being in the solved pattern at any given time?

The six center faces of the cube are fixed. By turning the faces all you can do is rearrange the corners and edges. If you took the cube apart, then there would be 8!=40,320 ways to arrange the eight corners, without respect to the orientation of each piece. Likewise, there are 12!=479,001,600 ways to arrange the 12 edges without regard to orientation.

There are 3 ways each corner can be oriented, for a total of 38=6,561 corner orientations. Likewise there are two ways each edge piece can be oriented, for a total of 212=4,096 edge orientations.

So, if we could take the cube apart, and rearrange the edge and corner groups, then there would be 8! × 12! × 38 × 212 = 519,024,039,293,878,000,000 possible permutations. However, not all of these permutations can be arrived at from the starting position by rotating the faces.

First, it is impossible to rotate just one corner and leave everything else the same. No combination of turns will achieve that. Basically, every action has to have a reaction. If you wish to rotate one corner, it would disturb the other pieces somehow. Likewise, it is impossible to flop just one edge piece. For these reasons, we have to divide the number of permutations by 3 × 2 = 6.

Second, it is impossible to switch two edge pieces without disturbing the rest of the cube. This is the hardest part of this answer to explain. All you can do with a Rubik's Cube is rotate one face at a time. Each movement rotates four edge pieces and four corner pieces for a total of eight pieces moved. A sequence of rotations can be represented by a number of piece movements divisible by 8. Often a sequence of moves will result in two movements canceling each other out. However, there will always be an even number of pieces moved with any sequence of rotations. To swap two edge pieces would be one movement, an odd number, which can not be achieved with the sum of any set of even numbers. Mathematicians would call this a parity problem. So we have to divide by another 2 because two edge pieces cannot be swapped without other pieces being disturbed.

So there are 3 × 2 × 2 = 12 possible groups of Rubik's Cube permutations. If you disassembled a Rubik's Cube and put it back together randomly, there is a 1 in 12 chance that it would be solvable. So the total number of permutations in a Rubik's Cube is 8! × 12! × 312 × 212 / 12 = 43,252,003,274,489,900,000. If you had seven billion monkeys, about the human world population, playing randomly with the Rubik's cube, at a rate of one rotation per second, a cube will pass through the solved position on average once every 196 years.

Links

I was playing Hearts and was dealt 10 of them. What are the odds of that?

For those unfamiliar with the rules of Hearts, play starts with dealing 13 cards each to four players. The hearts suit is significant to the game, so how many you get is important. The following table shows the odds of being dealt 0 to 13 hearts.

Probability of 0 to 13 Hearts out of 13 Cards

| Hearts | Combinations | Probability | Inverse |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 1 | 0.0000000000016 | 1 in 635,013,559,600.0 |

| 12 | 507 | 0.0000000007984 | 1 in 1,252,492,228.0 |

| 11 | 57,798 | 0.0000000910185 | 1 in 10,986,773.9 |

| 10 | 2,613,754 | 0.0000041160601 | 1 in 242,950.8 |

| 9 | 58,809,465 | 0.0000926113531 | 1 in 10,797.8 |

| 8 | 740,999,259 | 0.0011669030492 | 1 in 857.0 |

| 7 | 5,598,661,068 | 0.0088166008164 | 1 in 113.4 |

| 6 | 26,393,687,892 | 0.0415639752774 | 1 in 24.1 |

| 5 | 79,181,063,676 | 0.1246919258321 | 1 in 8.0 |

| 4 | 151,519,319,380 | 0.2386080062219 | 1 in 4.2 |

| 3 | 181,823,183,256 | 0.2863296074662 | 1 in 3.5 |

| 2 | 130,732,371,432 | 0.2058733541286 | 1 in 4.9 |

| 1 | 50,840,366,668 | 0.0800618599389 | 1 in 12.5 |

| 0 | 8,122,425,444 | 0.0127909480376 | 1 in 78.2 |

| Total | 635,013,559,600 | 1.0000000000000 |

This question was raised and discussed in the forum of my companion site Wizard of Vegas.

For casino promotions that still use regular tickets in a real drum (not the electronic ones) where you print your tickets at the players desk and put them into the drum -- do you bend / crease your tickets before you put them into the drum? Do you think that the bent ones have a better chance of being picked?

I hope you're happy. To answer this question, I bought a big roll of tickets at the Office Depot. Then I put 500 of them in a paper bag, half folded in half, at about a 90-degree angle, and the other half unfolded. Then I had six volunteers each draw 40 to 60 of them one at a time, with replacement, as I recorded the results. Here are the results.

Drawing Ticket Experiment

| Subject | Folded | Unfolded | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | 25 | 50 |

| 2 | 38 | 22 | 60 |

| 3 | 25 | 15 | 40 |

| 4 | 34 | 16 | 50 |

| 5 | 27 | 23 | 50 |

| 6 | 26 | 24 | 50 |

| Total | 175 | 125 | 300 |

So, 58.3% of the tickets drawn were folded!

If it's assumed that folding had no effect, then these results would be 2.89 standard deviations away from expectations. The probability of getting this many folded tickets, or more, assuming folding didn't affect the odds, is 0.19%, or 1 in 514.

I might add the subjects who drew tickets hastily were much more likely to draw folded ones. Those who carefully took their time with each draw were at or near a 50/50 split.

So, my conclusion is definitely to fold them.

For discussion about this question, please visit my forum at Wizard of Vegas.