Pico de Orizaba

At 1:00 a.m. on January 11, 2024, I set out on what would be one of my biggest mountaineering challenges – Pico de Orizaba. Orizaba is Mexico’s highest peak at 18,491 feet (5,636 meters). This would shatter my previous high-altitude record of 17,160 feet set on Iztaccíhuatl, Mexico’s third highest peak, which I climbed on February 20, 2016. Orizaba is also the third highest peak in all of North America.

The idea to climb Orizaba has been in my head for a long time. In 2016 it was my plan to climb it along with Iztaccihuatl. My friend Susan and I hiked Iztaccihuatl first but after that I was exhausted and not feeling well, so we decided to nix Orizaba and relax in the city of Puebla instead. However, Orizaba has taunted me ever since. Once I make a goal of something I may take a while to achieve it, but I usually do.

Fast forward to March 19, 2023 and I was climbing White Pinnacle, one of my favorite short and steep scrambles in Red Rock, the recreation area west of Las Vegas. This is a seldom climbed peak, but this day I happened to meet another group near the top, including a man named Celso. When I learned he lived near Mexico City, I asked if he had ever hiked Pico de Orizaba. He said in Spanish that he had not but wanted to. I asked if he would be interested in organizing a trip and he surprisingly said “yes.”

Celso did indeed organize a trip with several people on the list. However, after the usual drop-offs, the list came down to Celso, his friend Florente, my friend Beatriz and me. On January 6, 2024, I flew Viva Aerobus, which I highly recommend, to Mexico City. Jan. 7, I spent fooling around Mexico City. Jan. 8, I spent mostly in travel to Malinche, Mexico’s sixth highest mountain. Jan 9, the four of us successfully climbed Malinche. I write about that in my Jan. 11, 2024 newsletter. Jan. 10 was another transit day, where I spent part of it in the charming town of Huamantle.

The day before, we picked up two local guides and hired a driver to get us to the Refugio de Pierda (rock refuge), a public shelter at the foot of Orizaba. The reason for the driver is the dirt road leading to the Refugio is long and brutal. Celso’s car would never have made it, not to mention it wasn’t large enough for six people. It is also an option to hike instead of taking this road. I probably should have taken that option as the three-hour drive was not much faster than walking speed. On the way, we passed another group whose car didn’t make it. They pushed it to where it at least wasn’t blocking the road and we drove them the rest of the way up. After that experience, I would only attempt this road in a rugged 4x4 vehicle.

We arrived at the Regugio around 3:00 p.m. on January 10, where I rested and got my pack ready for a 1:00 a.m. start the next day. I could see other guides making their guests hot dinners on camping stoves. All I got was a lukewarm cup of hot chocolate. Usually, at this point, there is a gear check and pep talk by the guides about what to expect, but we received none of that.

I took a melatonin pill to help get to sleep. It was helpful, but I still was somewhere in the grey area between being awake and asleep until about 11:00 p.m. when the alarms of other groups went off for a midnight start. It was hard to sleep through that commotion, so I started to get ready too for our 1:00 a.m. start. By about 12:30, I was ready to go and sat around for about 45 minutes as the rest of the group prepared. In retrospect, I think we should have left at midnight too, when the other groups did, instead of having to try to sleep through their commotion getting ready.

The first five hours of the hike were steep, cold and in the dark. There was no moon to help. As it got colder and icier, Beatriz was showing difficulty going further. She said she couldn’t make it. In the interest of her safety, I volunteered to go back down with her if one of the guides would take us, as I had no idea of the route in the dark. However, the guides had none of that idea and kept going up, pulling her up with a piece of rope.

We made very slow process in this section and the group got scattered all over the place. It was hard to tell who was whom (is that the correct English?) in the dark because everybody was completely covered in many layers of clothing. At this point, what should have happened was the guides should have divided the group, with one taking the stronger guests further and the other taking those who were suffering from the conditions and obviously wouldn’t make the summit back down. Otherwise, what is the point of having two guides? However, both our guides kept quietly going up. They were both personally going for the summit and our safety was secondary. Yes, they helped us up, but I think they only did so until the sun came out so they could more safely abandon those of us who couldn’t go on.

Shortly after the sun rose, we were at the base of the glacier. We could see other groups making their way up like ants. At this point, if I were in charge, I would have stopped the group for a rest and a pow-wow about our options. Of the four guests, our speed and stamina were all different. As before, I think the option should have been given to split up the guides with one going for the summit and the other returning back down the mountain. It seemed to me that Florente and I had the energy to make it while Celso and Beatriz did not. However, the two guides kept climbing without comment.

I kept going. The guides took a strange turn the left, deviating from the path the other groups were going. Why? I have no idea to this day. Then they suggested we take off our packs for the summit push, to lighten our loads. In retrospect, this was a bad idea. Our packs had our water, extra clothing and who knows what else we might need. Distance-wise we may have been close, but at this altitude we were still about two hours from the summit, assuming a good pace.

Maybe it’s easy to say in retrospect, but I foolishly took this suggestion and left my pack with the others and kept on going. From that point, it was a steep slog the rest of the way. At this altitude, every step was a struggle. I estimate I made about three steps per minute. It wasn’t easy, but I kept going. At this point, Celso and Beatriz had dropped off. I assumed they were together. Celso was a capable and experienced mountaineer. Beatriz would be safe with him.

One step after another is all I could do. At this point, I was definitely the weakest link of the four left. Florente and the two guides were quite a way ahead of me, but never got so far ahead that I lost sight of them. I might add that in my research for Orizaba, every source I read said there were crevasses on the glacier and advised roping up. Did we? Nope. Speaking of rope, one of the two ropes used by the guides was made of twine.

After about two hours of this, I had to take a break to go #1. This was about 200 vertical feet from the summit. I put my heavy mittens on a small rock outcropping and did what I had to do. Big mistake. Half-way through a gust of wind took them sliding hundreds of feet down the mountain past the point I could even see them. It was very cold. I did have a back-up pair of lighter gloves, but they were in my pack I left down below.

So, I yelled for help. The two guides ignored me, pretending they couldn’t hear me. Florente did come down to where I was. I explained what happened and said I couldn’t risk continuing without my mittens. He kindly took off his and gave them to me, without comment. His gloves were very small but would have to do.

Here, I was then put in a difficult spot. I was already holding up Florente by going so slowly. If I continued to go up, his hands would be exposed to the cold even longer. Florente is a tough man and probably could have taken it. However, I thought the right thing to do was to go down. It would have been nice if one of the guides had descended with me in the interests of safety, but neither of them even came down to discuss the matter. It was obvious they were going for the summit and the clients could go back by themselves if they couldn’t make it.

Down I went. This was not easy as the ice was as hard as plastic in places, making it difficult to stick the ice axe in it for safety. However, I traversed around and managed to find soft ice sections the way down. I was extremely thirsty and ate some ice to quench my thirst.

Eventually, I found my way to the backpacks. Along the way I found a hiking pole. At least I wasn’t the only fool who let their gear slide down the mountain. At my pack, I had a much-needed drink of water and put on my own back-up gloves. This was a relief as Florente’s were too small. I then saw Celso nearby and went down further to talk with him.

Celso was full of questions about what was going on and who was where. In my lousy Spanish, I explained what I knew as best as I could. I asked where Beatriz was. He didn’t know. After some discussion, which wasn’t easy with my level of Spanish, we could see somebody was descending the glacier. The other groups were long since done with this section, so it was probably either one of the guides or Florente.

We waited for the mystery person to get down to us. It was one of the two guides. The first time they had ever been apart. He explained the other two wanted to take pictures. This made me regret my decision to descend if Florente didn’t mind staying longer on the summit without his gloves. However, that was water under the bridge. The three of us made our way down.

Making our way down was harder than expected. It turned out to be a sunny day, melting ice into water, which made for a lot of mud. I was feeling rather loopy from the high altitude and exhaustion so had to take a lot of breaks going down. Going up the ice was nice and firm, but going down was endless scree, ice and mud. The route was not obvious. The guide seemed to be improvising as we went down. Although we went up in the dark, I strongly suspect we got off course and went down the wrong way.

When the Refugio came within sight, the guide took off. Celso and I made our way the remainer of the journey, including down a steep screen slope. Yes, I’m quite sure we didn’t go up this way. When we finally reached the Refugio, it was 4:00 p.m., 15 hours after we started walking.

Beatriz was inside waiting. I thought she would be mad at being abandoned, but she wasn’t. I had a whole apology rehearsed in my head in Spanish, but she shrugged it off after the first two words, “lo siento.”

It turns out that Beatriz really had been abandoned. After waiting in the cold, she had decided to descend on her own. Then she got lost. Then she started screaming for help. Fortunately, a guide from another group heard her and lead her down from there. Back at the Refugio, she was in good spirits. If I were in her shoes, I would have been angry. Despite her having no hard feelings, I continue to judge myself harshly for my part in the chaos of the whole venture which lead to her being left to fend for herself.

Eventually Florente and the other guide returned. The driver was waiting for us and we made the drive back quietly. The guides probably sensed I was unhappy with them. When we got back and it was time to pay them, I didn’t tip them a single peso. Neither did I get any sarcastic “gracias.” It was a chilly silence between them and me.

Back in Las Vegas, I asked Beatriz if she happened to have any information about the guide from the other group that did get her down. I figured she might as they were chatting in the Refugio when I finally made it down. She did. I made contact and he said I could relay his information. His name is Pedro Loma Ibáñez and his number is +52-222-360-8093. Other than the story as told here, I can’t personally vouch for him. However, for what he did do for Beatriz, he gets a lot of points from me and I’m happy to give him a plug. If you’re interested in hiring him as a guide, please be informed he speaks only Spanish.

Do I plan to go back? Probably not. Maybe, if the opportunity to go with a good group comes to me on a silver platter. However, it probably won’t. At 58, I’m also getting too old for this. Future adventures are likely to be less dangerous and more social. I would like to do some of Mexico’s other big volcanoes, but I got close to the summit of Orizaba and I think that is good enough for me. I didn’t summit, but I feel I did Orizaba. In closing, here are some pictures from the trip. I also plan to put together a YouTube video soon.

Orizaba as seen from Tlachichuca, the staging point for our trip.

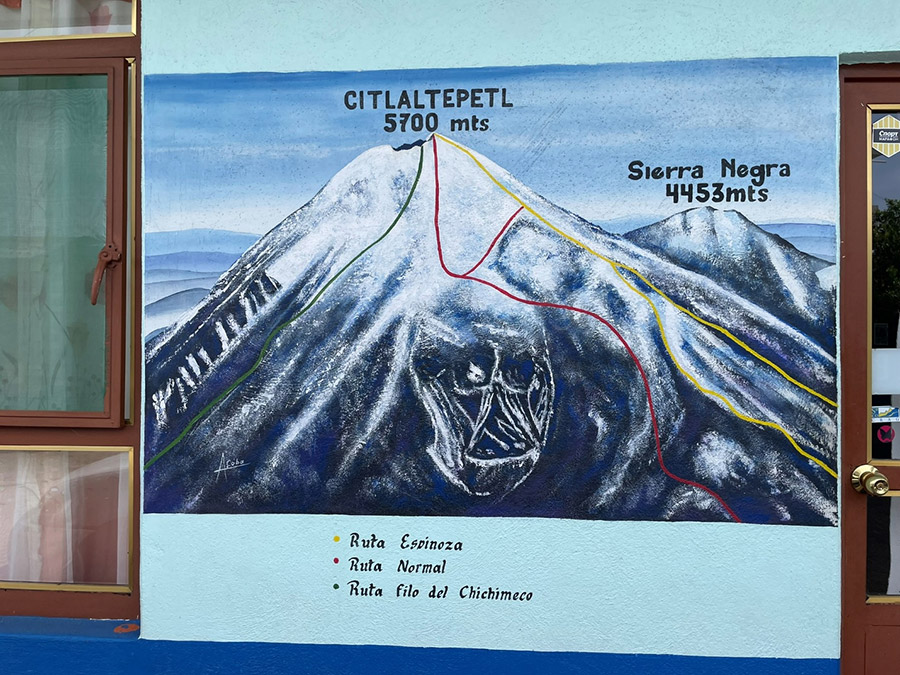

This is a map of Orizaba seen at the place we rented the car and driver. Citlaltepetl is the name of the mountain in the original native language, as opposed to Spanish.

Here I am the day before we started our hike, with the summit in the far distance.

Refugio de Pierda

The beginning of the trail. It did not stay on concrete for long. The route is supposed to go up the gully, but on the way down we somehow managed to be far up the slope on the right.

This is the highest picture taken of me on Orizaba, or anywhere for that matter. After this point, taking pictures was the least of my concerns. This picture portrays how steep the glacier was.